- Home

- Peter Swanson

Eight Perfect Murders Page 2

Eight Perfect Murders Read online

Page 2

Despite this, I somehow began to see my “Perfect Murders” piece—not yet written—as more important than it really was. I’d be setting the tone for the blog, announcing myself to the world. I wanted it to be flawless, not just the writing, but the list itself. The books should be a mix of the well known and the obscure. The golden age should be represented, but there should also be a contemporary novel. For days on end, I sweated it out, tinkering with the list, adding titles, subtracting titles, researching books I hadn’t yet read. I think the only reason I ever actually finished was because John started to grumble that I hadn’t published anything on the blog yet. “It’s a blog,” he’d said. “Just write a list of goddamn books and post it. You’re not getting graded.”

The post went up, appropriately enough, on Halloween. Reading it now makes me cringe a little. It’s overwritten, even pretentious at times. I can practically taste the need for approval. This is what was eventually posted:

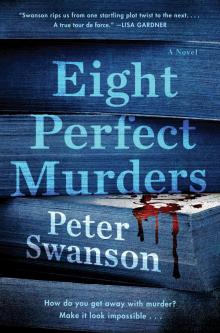

Eight Perfect Murders

by Malcolm Kershaw

In the immortal words of Teddy Lewis in Body Heat, Lawrence Kasdan’s underrated neo-noir from 1981: “Any time you try a decent crime, you got fifty ways you’re gonna fuck up. If you think of twenty-five of them, then you’re a genius . . . and you ain’t no genius.” True words, yet the history of crime fiction is littered with criminals, mostly dead or incarcerated, who all attempted the near impossible: the perfect crime. And many of them attempted the ultimate perfect crime, that being murder.

The following are my choices for the cleverest, the most ingenious, the most foolproof (if there is such a thing) murders in crime fiction history. These are not my favorite books in the genre, nor do I claim these are the best. They are simply the ones in which the murderer comes closest to realizing that platonic ideal of a perfect murder.

So here it is, a personal list of “perfect murders.” I’ll warn you in advance that while I try to avoid major spoilers, I wasn’t one hundred percent successful. If you haven’t read one of these books, and want to go in cold, I suggest reading the book first, and my list second.

The Red House Mystery (1922) by A. A. Milne

Long before Alan Alexander Milne created his lasting legacy—Winnie-the-Pooh, in case you hadn’t heard—he wrote one perfect crime novel. It’s a country house mystery; a long-lost brother suddenly appears to ask Mark Ablett for money. A gun goes off in a locked room, and the brother is killed. Mark Ablett disappears. There is some preposterous trickery in this book—including characters in disguise, and a secret passage—but the basic fundamentals behind the murderer’s plan are extremely shrewd.

Malice Aforethought (1931) by Anthony Berkeley Cox

Famous for being the first “inverted” crime novel (we know who the murderer and victim are on the very first page), this is essentially a case study in how to poison your wife and get away with it. It helps, of course, that the murderer is a country physician with access to lethal drugs. His insufferable wife is merely his first victim, because once you commit a perfect murder, the temptation is to try another one.

The A.B.C. Murders (1936) by Agatha Christie

Poirot is investigating a “madman” who, it appears, is alphabetically obsessed, killing off Alice Ascher in Andover followed by Betty Barnard in Bexhill. Etcetera. This is the textbook example of hiding one specific premeditated murder among a host of others, hoping that the detectives will suspect the work of a lunatic.

Double Indemnity (1943) by James M. Cain

This is my favorite Cain, mostly because of the grim fatalistic ending. But the murder at the center of the book—an insurance agent plots with femme fatale Phyllis Nirdlinger to off her husband—is brilliantly executed. It’s a classic staged murder; the husband is killed in a car then placed on the train tracks to make it look as though he fell off the smoking car at the rear of the train. Walter Huff, her insurance agent lover, impersonates the husband on the train, ensuring that witnesses will attest to the murdered man’s presence.

Strangers on a Train (1950) by Patricia Highsmith

My pick for the most ingenious of them all. Two men, each with someone they want dead, plan to swap murders, ensuring that the other has an alibi at the time of the murder. Because there is zero connection between the two men—they briefly talk on a train—the murders become unsolvable. In theory, of course. And Highsmith, despite the brilliance of the plot, was more interested in the ideas of coercion and guilt, of one man exerting his will on the other. The finished novel is both fascinating and rotten to the core, like most of Highsmith’s oeuvre.

The Drowner (1963) by John D. MacDonald

MacDonald, my choice for underrated master of midcentury crime fiction, rarely dabbled in whodunits. He was far too interested in the criminal mind to keep his villains hidden until the end. The Drowner is an outlier, then, and a good one. The killer devises a way to drown his or her victims so that it looks exactly like an accident.

Deathtrap (1978) by Ira Levin

Not a novel, of course, but a play, although I highly recommend reading it, along with seeking out the excellent 1982 film. You’ll never look at Christopher Reeve in the same way again. It’s a brilliant, funny stage thriller that manages to be both the genuine article, and a satirical one, at the same time. The first murder—a wife with a weak heart—is clever in its construction, but also foolproof. Heart attacks are a natural death, even when they aren’t.

The Secret History (1992) by Donna Tartt

Like Malice Aforethought, another “inverted” murder mystery, in which a small cadre of classics students at a New England university kill one of their own. We know the who long before we know the why. The murder itself is simple in its execution; Bunny Corcoran is pushed into a ravine during his traditional Sunday hike. What makes it stand out is ringleader Henry Winter’s explanation of the crime—that they are “allowing Bunny to choose the circumstances of his own death.” They are not even sure of his planned route for that day but wait at a likely spot, wanting to make the death seem random instead of designed. What follows is a chilling exploration of remorse and guilt.

Truth is, it was a hard list to put together. I thought it would be easier to come up with examples of perfect murders in fiction, but it just wasn’t. That’s why I included Deathtrap, even though it’s a play and not a book. I’d actually never even read Ira Levin’s original script or even seen it onstage. I was just a fan of the film. Also, looking back on the list now, it’s clear that The Drowner, a book I really do love, doesn’t quite belong here. The murderer lurks at the bottom of a pond with an oxygen tank, then pulls her victim down into the depths. It’s a fun concept, but highly unlikely, and hardly foolproof. How does she know where to wait? What if someone else is at the pond? I suppose that, once pulled off, it is a crime that truly looks like an accident, but I think I just put the book on the list because of how much I love John D. MacDonald. I suppose I also wanted something slightly obscure, something that hadn’t been turned into a movie.

After I posted it, Claire told me she loved the writing, and John, my boss, was just relieved that the blog had been started. I waited for comments to appear, allowing myself brief fantasies in which the piece would start an online frenzy, blog readers chiming in to argue about their own favorite murders. NPR would call and ask me to come on-air to discuss the very topic. In the end, the blog piece got two comments. The first came from a SueSnowden who wrote, Wow!! Now I have so many new books to add to my pile!! and the second came from ffolliot123 who wrote, Anyone who writes a list of perfect murders that doesn’t have at least one John Dickson Carr on it obviously knows nothing about anything.

The thing about John Dickson Carr is that I just can’t get into those books, even though the commenter was probably right in calling out their absence. Carr specialized in locked-room murder mysteries, impossible crimes. It seems ridiculous now but at the time I was bothered by the opinion, probably because I agreed with it to a certain degree. I even considered a follow-up post—maybe

something like “Eight More Perfect Murders.” Instead, my next post was a list of my favorite mystery novels from the previous year, and I wrote the entire thing in about an hour. I also figured out how to link the titles of the books to our online store, and, for that, John was extremely grateful. “We’re just trying to sell books here, Mal,” he’d said. “Not trying to start arguments.”

Chapter 3

Agent Mulvey was holding a printed-out sheet of paper. I took it from her, glanced down at the list I’d written, then said, “I remember this, but it was a long time ago.”

“Do you remember the books you picked?”

I glanced down at the printout again, my eyes going immediately to Double Indemnity, and suddenly I knew why she was here. “Oh,” I said. “The man on the train tracks. You think that’s based on Double Indemnity?”

“I think it could be, sure. He was a regular commuter. Even though he’d been killed elsewhere, it was made to look like he’d jumped off the train. When I heard about it, it made me immediately think of Double Indemnity. The movie, anyway. I haven’t read the book.”

“And you’re coming to me because I’ve read the book?” I said.

She blinked rapidly, then shook her head. “No, I’m coming to you because when I realized that maybe this crime was mimicking a movie, or a book, I did a Google search that included Double Indemnity and The A.B.C. Murders together. And that’s how I found your list.”

She was watching me expectantly, making eye contact, and I felt my own eyes skidding away from hers, taking in the large expanse of her forehead, her nearly invisible eyebrows. “Am I a suspect?” I said, then laughed.

She leaned back a little in her chair. “You’re not an official suspect, no. If that were the case, then it wouldn’t just be me here questioning you. But I am investigating the possibility that all these crimes were committed by the same perpetrator, and that that perpetrator is purposefully mimicking crimes from your list.”

“Mine can’t be the only list that includes both Double Indemnity and The A.B.C. Murders?”

“To tell the truth, it pretty much is. Well, yours is the shortest list that contains them both. Both books were on other lists together, but those lists were all much longer, like there was one called ‘a hundred mysteries you need to read before you die,’ that sort of thing, but yours jumped out. It’s about committing the perfect murder. Eight books are mentioned. You work at a mystery bookstore in Boston. All the crimes have happened in New England. Look, I know it’s probably all a coincidence, but I thought it was worth following up.”

“I get that it’s somewhat clear someone is copycatting The A.B.C. Murders, but a body found near the train tracks? That seems a stretch to say that’s from Double Indemnity.”

“Do you remember the book well?”

“I do. It’s one of my favorites.” This was true. I’d read Double Indemnity around the age of thirteen and was so thrilled by it that I sought out the film version with Fred MacMurray and Barbara Stanwyck that was made in 1944. That film led me down a rabbit hole of film noirs, my teenage years spent seeking out video stores that stocked classic film. Of all the noirs I saw because of Double Indemnity, none of them topped that first viewing experience. Sometimes I think the Miklós Rózsa score to that movie is permanently embedded in my brain.

“On the day that Bill Manso’s body was found on the tracks, one of the emergency windows on the train had been busted open, near to where the body was found.”

“So, is it possible he really did jump?”

“Not a chance. The scene-of-crime officers could tell that he’d been killed in a separate location and driven to the tracks. And the coroner confirmed that he’d died from blunt force trauma to the head, probably from some kind of weapon.”

“Okay,” I said.

“That means that someone, probably the person who killed him, or an accomplice, was on the train, and smashed the emergency window to make it look like he’d jumped.”

For the first time since we’d started talking, I felt a little jolt of alarm. In the book, and the movie as well, an insurance agent falls for the wife of an oil executive and, together, they plot to murder him. They do it for each other, but also for the money. The insurance agent, Walter Huff, fakes an accident policy on Nirdlinger, the man they plan to murder. Included in the policy is a “double indemnity” clause that doubles the amount of the payoff if death occurs on a train. Walter and Phyllis, the unfaithful wife, break the husband’s neck in a car, then Walter poses as Nirdlinger and goes onto the train, himself. He wears a fake cast on his leg, and has crutches, since the real Nirdlinger had recently broken his leg. He figures that the cast is perfect because other passengers will remember seeing him, but not necessarily remember seeing his face. He goes to the smoking car at the back of the train and jumps off. Then Walter and Phyllis leave the dead man by the tracks, so it looks as though he fell.

“So, you’re saying it was definitely made to look like the murder from Double Indemnity?” I said.

“I am,” she responded. “I’m the only one, though, the only one who’s convinced of the connection.”

“What were these people like?” I asked. “The people who were killed.”

Agent Mulvey glanced toward the drop ceiling of the bookstore’s back room, then said, “As far as we can tell, there’s no way to connect them, besides the fact that all the deaths happened in New England, and besides the fact that they seem to be copycat murders from fictional sources.”

“From my list,” I said.

“Right. Your list is one possible connection. But there’s also a connection . . . it’s not really a connection, more of a gut feeling on my part, that all the victims . . . weren’t bad, exactly, but weren’t good people. I’m not sure any of them were really well liked.”

I thought for a moment. It was getting darker in the back room of the bookstore, and I instinctively checked my watch, but it was still early afternoon. I looked back toward the stockroom, where two windows looked out onto the back alley. Snow had begun to pile in both of them and the portion of outside that I could make out through the windows was as dark as dusk. I turned on my desk lamp.

“For example,” she continued. “Bill Manso was a divorced investment broker. The detectives who interviewed his grown children said they hadn’t seen him in over two years, that he wasn’t exactly the paternal type. It was clear that they disliked him. And Robin Callahan, as you’ve probably read, had been pretty controversial.”

“Remind me,” I said.

“I guess a number of years ago she broke up a marriage of one of her co-workers. And, subsequently, her own marriage. Then she wrote a book against monogamy—this was a while ago. A lot of people don’t like her. If you google her name . . .”

“Well . . .” I said.

“Right. Everyone has enemies now. But to answer your question, I think it’s a possibility that everyone who has been killed so far was a less-than-stellar person.”

“You think that someone read my list of murders,” I said, “then decided to copy the methods in them? And they wanted to make sure that the people they were killing somehow deserved to die? Is that your theory?”

She pushed her lips together, making them even more colorless than they already were, then she said, “I know it sounds ridiculous—”

“Or you think that I wrote this list, and then decided to test out the murders for myself?”

“Equally ridiculous,” she said. “I know it is. But it’s also unlikely, isn’t it, that someone would copy a plot line from an Agatha Christie novel, and at the same time someone would stage a train murder from a . . .”

“From a James Cain novel,” I said.

“Right,” she said. My desk lamp has a yellow-tinged bulb, and in the glow from it she looked like she hadn’t slept in about three days.

“When did you make the connection between these crimes?” I asked.

“You mean, when did I find your list?”

“I guess so. Yes.”

“Yesterday. I’ve already ordered all the books, and I’ve read all their plot summaries, but then I decided I’d come directly to you. I was hoping you might have some insight, that maybe you’d be able to connect some other unsolved recent crimes to your list. I know it’s a long shot . . .”

I was looking down at the printout she’d given me, reminding myself of the eight books I’d picked. “Some of these,” I said, “you couldn’t exactly copy the murders from them. Or you could, but they’d be hard to spot.”

“What do you mean?” she said.

I scanned the list. “Deathtrap, the play by Ira Levin. Do you know that one?”

Before She Knew Him

Before She Knew Him Every Vow You Break

Every Vow You Break Eight Perfect Murders

Eight Perfect Murders Rules for Perfect Murders

Rules for Perfect Murders Her Every Fear

Her Every Fear The Kind Worth Killing

The Kind Worth Killing All the Beautiful Lies

All the Beautiful Lies The Girl with a Clock for a Heart: A Novel

The Girl with a Clock for a Heart: A Novel